How is murder reported in the Egyptian Gazette?

For my analysis project, I wanted to observe how murder was reported in the Egyptian Gazette. To gauge whether or not this was a feasible topic within the Gazette, I began with the simple query: //p[contains(., ‘murder’)]/text().

This enabled me to find all of the paragraphs containing the word “murder,” as well as surrounding text to gather some more details from the search. This search yielded about 800 items, so it was clear that murder was present enough in the Gazette to do some research with. This query was appropriate for a rough estimate of murder in the Gazette, but not much else. Since it looks for a paragraph containing the word murder, it can actually count the same case of murder multiple times if it is mentioned throughout several paragraphs. I knew that I had to get more specific with my topic, but finding that murder was at least relatively relevant within the Gazette was a good start.

Finalizing a Topic

After the initial stage of my project, I considered more deeply what exactly about murder that I wanted to focus on. I decided on an approach that would use murder as a measure of how reputable the Egyptian Gazette was for news. To do so, I would first evaluate the Gazette’s colonial bias against Egyptians (referred to as “natives”) by seeing if there was any difference in the reporting of native murders compared to non-native murders. The second criteria which I would use to evaluate the Gazette would involve comparing the number of recorded murders per year to the number of actual murders per year, as provided by the Egyptian Consul General papers.

More Querying

To begin these queries, I had to first determine what vocabulary would be most effective for searching. While the word “murder” had come to mind first, other words such as “homicide” and various forms of “kill” were used to describe these events. To evaluate which term was the most frequently used, I searched the following: count(//div[contains(.,’murder’)])

Where the word “murder” is would be interchanged for both kill and homicide to count the instances of these words. After a search of all three terms I found that murder returned 88 divs, kill returned 406 divs, and homicide returned zero divs. While it seemed that forms of the word kill were most prevalent, I read through about twenty of the results, and they were nowhere near as relevant as those that the term “murder” had returned. Most of the divs containing some form of kill either contained “murder” elsewhere in the paragraph (if it was describing a murder) or were more relevant to war. Since instances of war and other killings in non-murderous contexts (more common than it may seem) were far too common with the search including the word kill, I decided to stick with my original search of the term murder.

To find the instances of native murders, I wanted to ensure I was using the correct vocabulary for that search as well. I had seen native and Arab most commonly used within the paper to refer to the Egyptians, so I decided to see if “Arab,” “native,” or “Egyptian” would yield the most results. For this to be relevant within the context of my project, I searched the instances of these words occurring in the same paragraph with the word murder. The query is as follows: //div//p[matches(.,'murder', 'i')][matches(.,'native')]

Where the word “native” is was interchanged with the other two words. Within paragraphs that contained “murder,” “native” appeared to be the most frequently occurring of these terms.

Now that I had a query that effectively found all of the instances of murder involving a native, I copied the results into Sublime Text and shaved them down to the date and the relevant text. I then went through all of the results and put them into an Excel sheet, noting the date of the report, who (as in what nationality) was murdered, who was responsible for the murder, and where the murder occurred. Some of the results were eliminated because they were regarding attempted murder, war, or lacked necessary information.

After identifying all of the cases of murder in which Egyptians were either the victim, perpetrator, or both, I needed a way to identify all of the other murders in the Gazette. After some tries, I reached the following query: //div[@type="page"]/div[not(@feature="wire")]//p[matches(.,'murder', 'i') and not(matches(.,'native', 'i'))]

While not perfect, this query is able to find paragraphs containing murder that do not also contain the term native. In an attempt to hopefully eliminate news from other countries, I excluded divs with the feature “wire,” because I was noticing lots of telegrams reporting international murders within the results. This query does not account for multiple murders mentioned within separate paragraphs, nor does it eliminate uses of the word “murder” in a non-literal way (such as describing something as “murderous”). It did reduce the results down to about 424 items, which was a fairly believable number for the almost 3 1⁄2 years that are encoded.

Visualization & Analysis

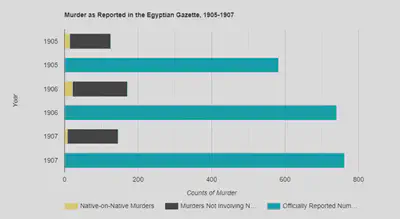

I chose to visualize this data in a way that would achieve three things: (1) show the proportion of native to non-native murders reported, (2) compare the total number of murder reports by the Egyptian Gazette to the actual number of murders per year and (3) show the overall trend of murder at this time in Egypt.

By closely analyzing the results of the search for “murder” and “native” together, I observed that there was not a single report of a native being murdered by an Englishman or other European. While I do not have a statistic to point to the occurrences of this, it seems highly unlikely that in three full years this never happened, especially given the imperial tensions at the time. The majority of the murders reported involving Egyptians were native-on-native violence. In each one of these cases, it was made clear that the murderer was also a native by a. directly calling them that, or b. naming them in full. If it was not clear that the murderer was a native, the murderer was either not mentioned, or just simply referred to anonymously as “the murderer,” even if they had been identified and proven guilty. This is an important finding because it shows that the Egyptian Gazette is inclined to report things that reflect poorly onto the Egyptians, but strays away from reporting incidences of Europeans killing the locals. I believe that this information discredits the Egyptian Gazette as a holistic source of Egyptian news at this time period because of its bias in reporting.

When looking at the graph, it’s clear that these native-on-native crimes make up only a small portion of which murders are being reported. Combined with murders not involving natives, most of what is reported in the Gazette makes up only roughly a quarter of all of the incidences of murder that are happening in Egypt yearly. There could be many explanations for this trend. The first is the way the Egyptian Gazette chooses to report. Perhaps they choose the murders that are more relevant or will make a more entertaining story to report. Maybe they choose not to report when an Egyptian has been killed by a European. The explanations could also lie in the cases themselves. There could be an element of privacy, or some cases may simply just not be well known.

The final trend that can be evaluated in this graph is the increasing number of murders in Egypt from 1905-1907. While the Gazette may not report this (their numbers seem to peak in 1906), the official documents of the Egyptian Consul General do show this. A pattern of increasing crime and civil unrest could be the result of a worsening environment between the Egyptians and the imperialist English power.