Analyzing importance in different wheat varieties in the Egyptian Gazette

Although agriculture is important in every society, it proved especially important in Egyptian culture. With life almost being centered on the Nile, taking advantage of the annual flooding of the Nile was necessary. Around the 19th century, Muhammad ‘Ali focused on revitalizing farming infrastructure in order to build massive, high efficiency farming systems that could support entire cities with surplus being up for trade. (Johnson 2015) The plan was extremely successful and was then carried on by his successors, leading Egypt to gain an edge in the world of agriculture.

Interest in control over the Nile’s floods grew from being purely motivated by farming based income and towards influence in Sudan. (Johnson 2015) After utilization of a cleverly placed dam, access to land in Sudan allowed for further expansion of irrigation systems and farmland which in turn boosted agricultural output. Increasing Egyptian yield was not all positive however, due to constant soil usage, soil quality rapidly diminished and pest problems started to grow. Despite agriculture providing a reasonable part of Egypt’s national income, there was a lack of well defined agricultural administration under the Cromer administration. (Johnson 2015) At this point more clear lines were drawn between the purpose of different crops with wheat being primarily for domestic consumption, and cotton being used as an export crop. Due to Egypt’s government being primarily British led, most agricultural policy was geared towards maximizing British income, meaning wheat farming took a backseat to cotton production meant for export. Due to wheat not being a “cash crop” in the same way cotton was, it didn’t continue to expand the same way cotton did as its purpose was mostly domestic. Despite all this however, Egyptians were extremely good at producing wheat, even being cited as being the best in the world at some point. (Gowayed 2009) Because of this, three wheat varieties were primarily grown: Tugari, Mawani, and Middling. Although information on these species of wheat is sparse beyond the context of Egyptian Gazette, what there is information on is prices.

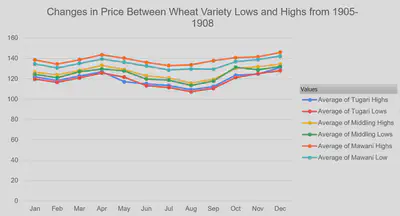

Pictured above is the monthly average of the highs and lows of the three different wheat varieties. Although nothing specifically stands out at first, there are a few abnormalities in the seemingly normal chart. First and foremost, year after year, Mawani wheat consistently outperforms the other two wheat varieties. I did research into why this could be, and found that Mawani wheat was the variety that was often exported, while the other two varieties were more specifically seen as domestic crops meant to feed the population. On top of this, Mawani wheat was subject to price fixing at high costs in order to maximize export income. (Bureau of Statistics 1918) Because of these factors, domestic variants stayed more reasonably priced than the Mawani (Export) variant of wheat. The data is mostly consistent outside of this besides the Mawani variant from July to September. While the two other varieties often dip in that period, Mawani holds strong. I wasn’t able to find any sources directly speaking on it, (in the newspaper and online), but with the understanding the Mawani was an export variety, it would make sense that since wheat can be stored near indefinitely, wheat would be sold in a consistent manner month after month to maintain price by storing surplus in bountiful seasons. Further research into the issue reveals that in late 1907 a group of British soldiers went pigeon hunting, and a stray shot hit and set fire to a village’s wheat supply. From the chart, there is no way to determine whether it affected wheat prices, it does provide valuable insight into the flammability of wheat in Egypt either as a result of how it is stored and/or how climate affects said flammability, proving it to be a real risk worth considering when storing wheat.

Although wheat was always significant throughout the history of Egypt, it did end up taking a backseat to cotton entirely by the start of 1902 due to wheat simply just being unable to keep up economically. Cotton was storable throughout all seasons and demand shot up during winters, giving cotton farmers a target to aim for that wheat farmers simply didn’t have due to lower, more consistent demand over the course of the year. Although wheat and cotton aren’t necessarily competitive goods, as they both serve different purposes, they did compete for the same production space, forcing wheat out of the agricultural spotlight. Wheat suffered at times due to policy often specifically targeting cotton export growth, which hurt wheat due to cotton taking priority. To some degree, because cotton was the more profitable endeavor, this benefitted the wheat industry as it meant the Egyptian locals maintained control of their industry rather than it being entirely dictated by European leaders. The most impactful takeaway from this research is that although wheat fell away from being Egypts most popular crop, it still maintained a consistent purpose in providing domestically season after season.

Sources

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101048820458.

https://d-nb.info/1000461033/34

Al-Rifai, N. Y. (2020). Denshawai and Cromer in the poetry of Ahmad Shawqi. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 7(3) 1- 27.