What is the Cultural Significance of Mummies in Early 20th Century Egypt?

Introduction & Research Question

Before my learning in this course, the only Egyptological concept I was somewhat familiar with was that of the mummy. Mummies are the remains of humans or animals that have been preserved through specific ceremonial practices, such as removing internal organs and wrapping their bodies with bandages. Growing up in modern Western culture, I was exposed to mummies in museums, history textbooks, and countless movies, TV shows, and books. I never learned about them in-depth, though. Furthermore, they seemed to be exploited for their “creepy” factor rather than their cultural significance. Time and time again, I witnessed mummies portrayed as monsters instead of valuable cultural artifacts.

Already faintly accustomed to this unfairness in the representation of Egyptian tradition, I was especially shocked when I realized that after encoding several issues of the Egyptian Gazette, I had not read a single mention of mummies. Based on the stereotypical portrayals of Egyptian culture in Western media, I expected plentiful discussions on mummies in the Gazette. This gap between stereotypical expectations and reality intrigued me; I instantly wanted to know more about mummies and their actual cultural significance beyond what American Hollywood films had led me to believe. With all this in mind, I decided to explore “What was the cultural significance of mummies in the early 20th century?” as my research question. I limited the scope of my findings to the early 20th century to better utilize our course’s repository of Gazette records.

Queries & Visualizations

I began my research with the following X-Path query:

//div[matches(.,'mummy', 'i')]/@feature

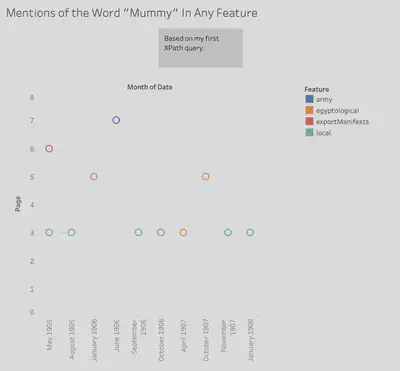

I started with this relatively broad query to find which features had the most frequent mentions of the word “mummy,” or at least to find some sort of other noticeable trend in the word use that could help me narrow my research scope in further queries. Based on the results from this query, I created the following data visualization.

As is evident in the graph, the query only yielded eleven issues with features that mentioned the word “mummy.” Based on this number, I inferred that many uses of the word probably occurred in segments of the Gazette that were not labeled as features. Whether this was due to human entry error in our course repository or not, I could tell that this query alone was not fruitful enough to serve as the sole basis for my research. A helpful conclusion I could draw from the results of this query, though, was that mentions of “mummy” occurred at a proportionally higher rate amongst the results on page three of the Gazette issues. This finding was not what I initially had in mind when I used a query focused on features, but I was grateful to have a starting point for the next query. I refined my second query to only search for word mentions on the third page of Gazette issues to see whether this would bring me more results, specifically because this query was not limited to segments labeled as features. My goal was for this next set of results to provide me with a richer variety of information that could help me ultimately answer my research question.

My second, more niche query ended up looking like this:

//div[@type="page"][@n="3"]//div[matches(.,'mummy', 'i')]

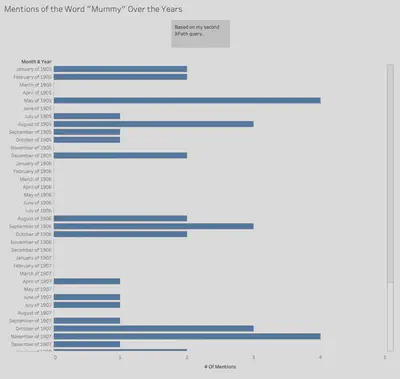

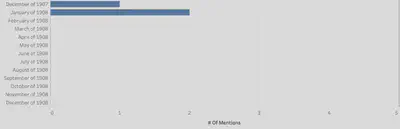

Much to my delight, this query yielded thirty-seven articles that mentioned my search term. I created the bar graph below to help me visualize this data and spot any trends.

It is worth noting that the visualized data above only portrays a proportion of total mentions of my search term because I confined the query to a specific page number rather than a raw word count. This proportional data, though, was immensely helpful in narrowing down the number of articles I could read that discussed mummies rather than just any Gazette item that happened to use the word “mummy.” Thirty-seven articles were substantial enough to provide me with further insight into the cultural significance of mummies in Egypt at the newspaper’s time while still being a manageable amount of data. Overall, I was pleased with the results of my second XPath query and felt that it provided sufficient material to move from the exploratory to the analytical phase of my project.

I began my analysis by ascertaining trends in the visualized data above. I found that “mummy” was used the most in 1905 with sixteen mentions, followed by seven in 1906, then a spike to twelve in 1907, and ultimately only two in 1908. Although this data would suggest a drastic decrease in interest in mummy-related topics, I could not draw any significant conclusions from the lack of mentions in 1908 due to the fact that our course repository does not have many issues from that year in general.

Furthermore, I tried to focus on the months of the word mentions to see if there were any times of the year when mentions were most frequent. However, I was unsuccessful in determining any rhyme or reason to the word mentions. None of the months or overall seasons experienced a higher rate of mentions than others. Ultimately, the only trend I could conclude from my visualized data was the lack thereof; from an analytical standpoint, the use of the word “mummy” seemed random and did not follow any visible patterns.

Data Interpretation & Supplementary Research

Once I read the articles yielded by my second XPath query in my next phase of analysis, I quickly noticed that at this point in Egyptian history, mummies were more of a cultural spectacle for other countries than a sacred practice for native Egyptians to prepare for the afterlife, as they were in ancient times. Most of the articles discussed mummies in relation to museum exhibits or the projects of American Egyptologists. For instance, in the article “The Pharaoh of the Exodus,” from the 1905-12-26 Gazette issue, it was recorded that “A discovery of the utmost importance has just been made by the well-known American Egyptologist, Mr. Theodore M. Davis, who has discovered in the valley of the Tombs of the Kings, the tomb of Mer-en Ptah, a pharaoh of the 19th dynasty … This pharaoh, who is also known as Meneptah, is thought by many to have been the pharaoh of the Exodus. His mummy was found in the tomb of Amenhotep II at Thebes.” I found this evidence of excavation work, and other articles like it, to be the most compelling because they demonstrated that the fascination with mummies during this time primarily came from foreigners rather than native Egyptians. Here is where I began to think that perhaps the mummy was more important to curious outsiders than the Egyptians themselves.

My interpretive conclusion grew as I read the remaining articles from my query. Many of them discussed European collectors of mummies, and one article entitled “Egyptian Mummies, No Fabrication” from the 1907-10-03 Gazette issue even divulged the easy accessibility of mummies: “Besides, the supply of mummies is practically inexhaustible and the price of an ordinary one is so low that a manufacturer in Paris could not box his mummy and send it to Cairo to be sold for the price that the genuine article can be bought at there, with its painted case and the certificate of the Cairo museum as to its genuineness.” Not only does the wide circulation and affordability of mummies in this newspaper excerpt point to their exploitation and spectacle nature, but the flippant tone of the writer suggests that mummies were not respected as culturally significant. The writer treated mummies as decorative commodities rather than artifacts of a practice that was sacred to ancient Egypt. Most of the articles fell under these larger categories of museums, exhibits, foreigners’ excavations, or foreigners’ mummy collections. The rest of the articles were random and largely insignificant, or sometimes redundant, such as the multiple articles referring to a sketch called “The Mummy and the Mummer,” written and performed by an Englishman. Even these seemingly unimportant articles further exemplify the fascination with and the spectacle nature of mummies in non-Egyptian cultures.

Once I had my preliminary conclusions formed from my research in the Gazette, I consulted secondary sources to see if they would substantiate or refute my findings. After sifting through many academic articles, I found a consensus with my notion that mummies were largely valued in the early twentieth century purely as a cultural spectacle and a means to exploit and objectify Egyptian culture, primarily by Europeans and Americans. In the article “Between Spectacle and Science: Margaret Murray and the Tomb of the Two Brothers”, it even discusses the popularity of mummy unwrappings in England at the early twentieth century. The article describes these public unwrappings as “public spectacles which displayed and objectified exotic artifacts” (Sheppard). Although the goals of some mummy unwrappings were rooted in scientific investigation, the vast majority of unwrappings served as entertainment, demonstrating a regard for mummies as culturally insignificant. In the article “Unswathing the Mummy: Body, Knowledge, and Writing in Gautier’s Le Roman de la momie”, I learned that this tradition of unwrapping mummies for public spectacle had spread throughout Europe, specifically in France. Curious as to when this trend in desecrating mummies for public interest began, I found an article called “Unwrapping the Past: Egyptian Mummies on Show” that detailed an “incredible rise [in the 1820s] in the acquisition of Egyptian mummies for souvenirs and as artefacts for collection and display. [Mummies were] treated more as commodities and historical specimens than as human remains, they were displayed, unwrapped, cut open and divested of their funerary goods, all in the name of knowledge” (Rogers). This source effectively traces the sparked interest in mummies and their degradation at the hands of non-Egyptian collectors, historians, and scientists to the early 1800s. It became apparent to me that the treatment of mummies as insignificant objects within and beyond the borders of Egypt far predated the issues of the Egyptian Gazette that we examine in this course.

Conclusion

My ultimate conclusion from my research in both the Gazette and outside academic sources is that mummies in the early twentieth-century were culturally insignificant, or at least were treated as such. Mummies seemed to derive their value as spectacles and commodities rather than artifacts that still served a critical purpose to their native culture.

However, a weakness of my digital research methods in this project is that my microhistorical data only drew from a limited-perspective source: the Egyptian Gazette. The Gazette was written and published by the English forces occupying Egypt rather than native Egyptians. Ergo, coverage of mummies and related Egyptological topics came from a highly biased source. These topics most likely were not treated as culturally significant as they would have been if the newspaper were run by the native Egyptian population. Broadening my microhistorical data pool to include newspapers written by native Egyptians would have allowed me a more advanced analysis and overall stronger research conclusion. Given the microhistorical data I had to work with, my research conclusions more appropriately answer the question of how culturally significant mummies were to the English forces in early twentieth-century Egypt rather than their significance in general. This issue of bias in my microhistorical source is especially crucial since my research question deals with qualitative rather than quantitative data. I had to rely on the written content in the Gazette to answer my sociological research question rather than numbers from the Gazette’s various tables and charts, which are not as directly impacted by the newspaper’s biases. Furthermore, the qualitative nature of my research question made finding numerical data to visualize for the project very difficult. I had to brainstorm which types of XPath queries would reveal data that would make sense or possibly lead to visible trends in a graph, which was complicated by my research question’s lack of adherence to any numerical concepts. If my research question was more inherently quantitative, I could have constructed more visually striking graphs that revealed more apparent trends in their data. Due to my research question’s reliance on qualitative over quantitative data, I found that much of the contextualization for the articles I yielded in my queries came from secondary sources rather than the Gazette.

Although some weaknesses arose in my research from the limited scope of my microhistorical source and the lack of quantitative qualities in my research question, there were some strengths in the digital research methods I used. It may have been difficult to create data visualizations in my project; however, I think my ability to construct visual representations of the concepts I discussed made the data easier to follow for readers. Additionally, these visualizations helped me to form a fundamental understanding of my research topic before diving into my secondary research. Moreover, I think my ability to pull specific quotes from the broader microhistorical source for this project helped substantiate my research findings for myself and readers. Due to the qualitative nature of my research question, I could find quotes from the Gazette that were relevant to my research and helped me reach a compelling conclusion with demonstrative ethos for readers. All in all, my research process was imperfect, but I think I found a sufficient answer to my initial research question through the microhistorical digital methods I learned in this course.

Works Cited

Lyu, Claire. “Unswathing the Mummy: Body, Knowledge, and Writing in Gautieris Le Roman De La Momie.” Nineteenth Century French Studies, vol. 33, no. 3, 2005, pp. 308–319., https://doi.org/10.1353/ncf.2005.0026.

Rogers, Beverley. “Unwrapping the Past: Egyptian Mummies on Show.” Popular Exhibitions, Science and Showmanship, 1840–1910, 2015, pp. 215–234., https://doi.org/10.4324/.9781315655123-19.

Sheppard, Kathleen L. “Between Spectacle and Science: Margaret Murray and The Tomb of the Two Brothers.” Science in Context, vol. 25, no. 4, 2012, pp. 525–549., https://doi.org/10.1017/s0269889712000221.