The Cotton Worm in Egypt from 1905 to 1907

Cotton has been an essential export from the Egyptian economy for centuries, sometimes being referred to as the country’s “white gold”. In the beginning of the twentieth century, there was a cotton worm epidemic that greatly threatened the cotton plants across all the Egyptian provinces. The Khedive made a national decree that informed the public of the cotton worm menace, and contained a call to action for citizens to band together to combat the cotton worm. One way that Egypt went about protecting their harvests from the cotton worms was to conscript local children to go out into the fields and pick the cotton worms and cotton worm larvae off the plant stems by hand. From the years 1905 to 1907, thousands of children were enlisted to help save the harvests in every cotton containing province. The amount of land that was affected by the cotton worms is measured in feddans, an arabic unit to measure land. One feddan is just under the size of one acre (1 feddan=1.03 acre). Within the Egyptian Gazette, there is a copy of the Khedivial Decree of the cotton worm menace, many articles containing information about the amount of feddans affected by the cotton worm and how much of the land was cleansed by a certain number of children, and other articles relevant to the cotton worm situation. By examining the amount of land affected, how much of that affected land was picked free of cotton worms and larvae, and how many children were working to get rid of the cotton worms, the general success of the movement against the cotton worm from 1905 to 1907 can be determined.

The Khedivial Decree, found in the 1905-03-01 edition of the Egyptian Gazette, informs that the plants infested with the cotton worm must be stripped and burned. It outlines that any able-bodied men from ages 9 to 17 must work in the fields to cleanse the cotton worm for a minimum salary that matched the market prices. Any child that refuses to work or commits any act of negligence while working could be fined and thrown in prison for up to a week. The Khedivial Decree was originally published in French and was translated to English via Google Translate. The Khedivial Decree shows the serious nature of the cotton worm menace, and how it posed a critical threat to all of Egypt. By taking such extensive measures like child conscription, it is evident that the Egyptian authority realized the potential danger of the cotton worm and the necessity to take drastic measures to avoid an even worse outcome.

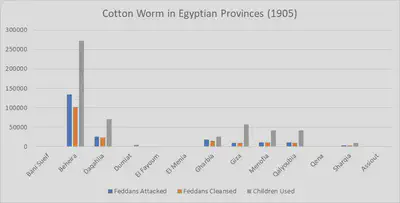

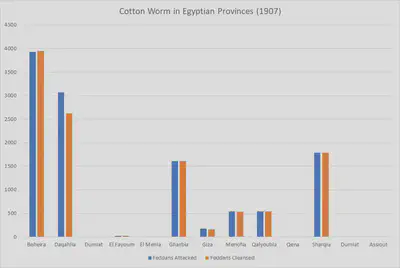

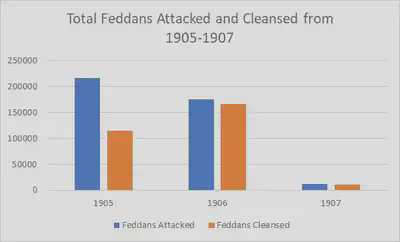

Articles titled “The Cotton Worm” in the Egyptian Gazette pop up pretty often in the “Local and General” section of page 3 and detail the latest reports on the cotton worm infestation. Cotton Worm articles show how many feddans are affected, and how many were cleansed, and sometimes how many children were used to do the work. The data these articles provide is the main method in tracking the progress of the fight against the cotton worm. Most of the articles appeared in the months of July and August.

Following are graphs of the amount of land that was attacked by cotton worm, how much was cleansed, and how many children were used to pick the worms.

Note: for 1906 and 1907, there was no report of the number of children used in the combat of the cotton worm.